“What gets measured gets managed.” So said Peter Drucker, the well-known management thinker. And it’s generally true. Unfortunately, when it comes to protecting the physical health of our workers from exposures that cause disease and death, we tend to count the corpses rather than focus on controlling the exposures that produce them.

Opinion

It’s time to up our game on preventing occupational diseases

And even then, that counting only goes on at national level in the Health and Safety Executive’s (HSE’s) annual statistics. Each year HSE reports on the national picture and the reported headline is always about the number of accident fatalities (123 in 2021/22)1. In the small print we read that 13,000 workers lose their lives each year to occupational disease. That’s 99 per cent disease and one per cent accidents. Every work-related death is a tragedy, but how come we seem to forget about the 99 per cent?

Steve Perkins: "It’s time to focus on prevention in workplace health so that the workers of the future won’t be doomed to repeating our failures of the past." Photograph: Steve Perkins Associates

Steve Perkins: "It’s time to focus on prevention in workplace health so that the workers of the future won’t be doomed to repeating our failures of the past." Photograph: Steve Perkins Associates

Did you know that the construction sector in Great Britain alone is responsible for 3,500 occupational cancer deaths, plus 5,500 new cases of occupational cancer each year? And at any one time there are some 74,000 construction workers with work-related ill-health, 54 per cent of which is musculoskeletal disorders?

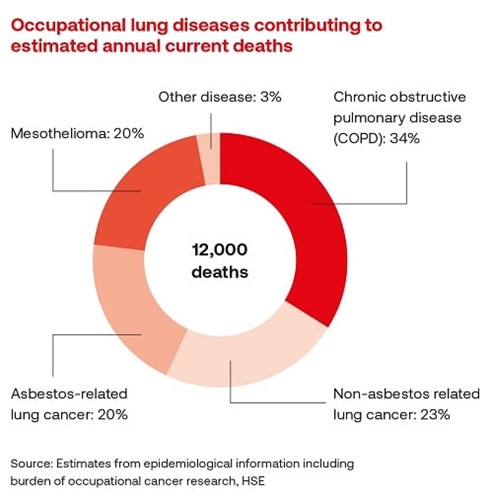

12,000 of those 13,000 fatalities across all sectors (that’s 92 per cent) are respiratory disease. Or to put it more bluntly – slowly suffocating to death. I know what that looks like at a personal level, having seen my own mum suffer and die with a chronic lung disease. And that is happening thousands of times all across the country, every year, due to entirely preventable exposures in the workplace. It’s just that these workers die ‘out of sight’, at home or in hospitals and care homes. They certainly don’t die in the workplace (or on the books) of the employer who exposed them. They are our hidden pandemic.

Some might say, “but this is all Grandad’s disease” – i.e. due to past asbestos exposures. In one sense I wish it were and then we could consign it to the past given the ban on asbestos use. Unfortunately, that’s not true. According to HSE, 40 per cent of those 12,000 respiratory fatalities are asbestos-related. The other 60 per cent are due to COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) and other cancers. That’s still a huge number.

So what are we measuring when it comes to health protection?

Or maybe a more pertinent question is, how do our current health, safety and wellbeing metrics impact on health protection?

Well, numbers of mental health first aiders or champions is certainly important, but wellbeing-related measures like that won’t have any impact on reducing the physical, chemical or biological workplace exposures that cause the occupational diseases I’m highlighting.

To put it bluntly, no amount of mindfulness will stop you getting silicosis or noise-induced hearing loss! (I’ll come to how wellbeing, occupational health and occupational hygiene work in relation to one another in a moment.)

60 per cent of work-related lung disease cases are due to COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Photograph: iStock

60 per cent of work-related lung disease cases are due to COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Photograph: iStock

And then there’s LTI, LTA, AFR… (otherwise known as the ‘Looking Good Indices’). All of which focus on accidents, not ill health. It could be argued that even in terms of preventing accidents these metrics are not a lot of help due to their lagging nature. They don’t reveal anything about what is being done now to reduce workplace risk and so decrease the likelihood of future accidents. But I digress; that’s a different article.

Well surely then, RIDDOR is the answer when it comes to health metrics and we all count RIDDOR reportable diseases? Unfortunately, RIDDOR is to health protection what AFRs are to accident prevention – seriously lagging! The key thing about the most serious occupational diseases is that they are ‘long latency’ – i.e. it can take years if not decades for many of them to develop. So, by the time the disease manifests, the damage is done and, because there are no cures for these diseases, it’s too late to stop them progressing.

The BIG picture of workplace health

I mentioned earlier that I’d look at how wellbeing, occupational health and occupational hygiene work in relation to one another. There are three broad, but overlapping, dimensions to workplace health:

The classic understanding of health at work comes under the banner of occupational health. This is the clinical arena that’s all about managing the health of workers as it is today. It covers the work of doctors and nurses on things like fitness for work, medicals and health surveillance.

Wellbeing is the second dimension of health at work. This is primarily about encouraging individuals to make healthy lifestyle choices and has benefits both for employees and employers.

The third dimension of health at work is occupational hygiene. This is all about protecting people from workplace health risks. These are the entirely preventable risks the workplace itself creates, which are regulated by the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974. Preventing ill health is all about controlling exposures; it’s not about clinical treatment or health promotion. It’s about protection.

Occupational hygienists are highly qualified applied scientists who deal with the anticipation, recognition, evaluation and control of workplace health risks. Theirs is a cross-cutting discipline encompassing aspects of physics, chemistry, biology, medicine, ergonomics, toxicology and engineering.

Is health, safety and wellbeing really protecting our workers’ health?

Let’s return to our original question. Someone once said, “the system you have is perfectly designed to give you the results you’re getting”. If HSE’s statistics are anything to go by, the ‘system’ for protecting worker health is pretty dysfunctional.

Unfortunately, these levels of serious occupational disease and death reported by HSE have been going on for decades and they’re generally not reducing. It seems to me that it’s hard to conclude anything other than the answer to our original questions is a resounding “No”. By any outcome measure, health, safety and wellbeing is currently not protecting our workers’ health.

As a senior manager at one of our clients put it, “health protection is still at the ‘hard hat’ stage!”

So what’s the answer?

Of course, it’s not all doom and gloom when it comes to workplace health protection; there are some great examples of good practice, most notably in construction from some of the major public infrastructure projects.

Health protection has been rising up the health, safety and wellbeing agenda in recent years, helped in large measure by the increasing focus on health in the previous and new HSE strategies4. Specific inspection initiatives on workplace exposures like silica and wood dust are to be welcomed in this regard.

But, if we want to get serious about improving worker health protection so that the 13,000 number does not continue as our legacy for decades to come, it’s going to require a lot more. My experience working in the construction sector as a strategic occupational hygiene, health and ergonomics consultancy indicates that nothing short of radical change and refocusing on health protection is required.

We use our Health Protection Culture Improvement model to guide our work, based on the mission of ‘Everyone Protected at Work’. To achieve this there are five key things an employer has to get right across their organisation. These are the critical success factors of health protection.

And if we’re starting from first base they tend to flow in a cycle; hazard awareness, moving into health ownership (right from the top of the organisation of course), then proper health risk management, real control improvement and finally protection assurance as the feedback mechanism.

Health Protection Culture Change

Underpinning these are five strategic enablers. These are the key tools we use to ensure the success factors are achieved: stakeholder engagement, leadership coaching, competent people, leading indicators and effective systems.

As you look at this you’ve probably noticed that apart from the ‘health’ word these are exactly the sort of management concepts you’d expect to see if we were talking about a strategic organisational approach to accident reduction. The difference is that what underpins this approach technically are the science-based skills and expertise of occupational hygiene and ergonomics, not occupational safety.

It’s time to focus on prevention in workplace health so that the workers of the future won’t be doomed to repeating our failures of the past.

Steve Perkins is the managing director of Steve Perkins Associates Limited, an occupational hygiene and health consultancy specialising in strategic workplace health solutions. Contact him at: steveperkinsassociates.com

Steve Perkins will be giving a presentation at the SHW Live exhibition in Farnborough, Hampshire, on 28–29 September, on ‘Changing Workplace Health Culture – M25 Healthier Highways’. He will be joined by Elaine Gazzini, technical and programme director at Connect Plus (M25). Register for free at: safetyhealthwellbeing.live

OPINION

Is workplace health safe in 2026?

By Kevin Bampton, BOHS on 10 February 2026

UK Government efforts to boost the economy and employment levels through approaches such as deregulation pose a serious threat to the country’s workplace safety standards and the health of our workforce.

How stress and burnout will shape the workplace in 2026

By Charlotte Maxwell-Davies, Mental Health UK on 09 February 2026

Burnout is rapidly becoming one of the nation’s most significant workplace challenges. It is emerging as a defining issue for organisations and wider society, as the UK contends with a long-term sickness crisis driven by poor mental health. Stress can be motivating in short bursts, but when left unmanaged it contributes to work absences and lost productivity, as well as presenting a clear risk to the health of workers.

A new year, a new approach to risk?

By Mike Robinson FCA, British Safety Council on 02 February 2026

The rulebook is becoming obsolete faster than we can rewrite it. While bureaucracies labour to update yesterday’s regulations, the world of work transforms daily.