The dire warnings about air pollution’s impact can leave us feeling scared and stuck. As a systemic problem there are limits to what individuals can do in isolation to protect themselves. But is that the full picture? What is the potential for individuals and businesses to support change?

Features

Air pollution – but what can you do?

Anna is a nurse in London. She cycles to work every day and enjoys vegan food and hiking. She hits most indicators of a healthy lifestyle, yet also scores highly on a breath monitor for carbon monoxide, something she uses on patients to assess their exposure to car exhaust fumes. “I cycle to work so am probably more exposed to air pollution. But I live in London – what can you do?” she shrugs.

Air pollution is a human made problem, but the power to change it to a large extent does not lie with the individuals who suffer the most. Photograph: iStock

Air pollution is a human made problem, but the power to change it to a large extent does not lie with the individuals who suffer the most. Photograph: iStock

It’s a question anyone who works or lives in a city must ask themselves. Though air pollution is a human made problem, the power to change it to a large extent does not lie with the individuals who suffer the most. Dr Gary Fuller has thought hard about this question in his book The Invisible Killer: The Rising Global Threat of Air Pollution – and How We Can Fight Back: “The voice of industry is always louder than the voices of people who suffer from poor air. Shifting this consensus is a job for all of us,” he writes, explaining that we can do this by our own actions, and by normalising low-pollution lifestyles.

“Shop local, join the debate: neighbourhood groups, residents’ associations, environmental groups, school parents’ associations, letters pages of newspapers and political parties are all places to bring about change. Trade unions are growing increasingly concerned about the air that outdoor workers breathe.”

Air pollution – the causes

Air pollution can be a problem anywhere, but it’s particularly an issue in cities. Manchester, Greater London and Birmingham all topped a 10 most polluted list of cities published in a report last year by the UK government. But, also, around 97 per cent of addresses in the UK exceed the WHO’s recommended limits for at least one of three key pollutants, according to research by Imperial College London.

What causes it? Road vehicles are one of the biggest contributors, producing nearly half of all nitrogen oxides. As tyres spin on roads, they also emit tiny particles of rubber and metal – called particulate matter – into the air we breathe. A quarter of these PM2.5s and PM10s come from vehicles.

It’s not just cars though. In early lockdown London experienced a spike in particulate matter in the air, even though cars were largely off the roads. This was because east winds blew polluted air over from factories and power plants based in mainland Europe. As Fuller writes: “Air pollution does not even recognise borders, so doesn’t need to even be created by a town for its inhabitants to experience the effects. Its mobility means that the air I breathe in Southern England might have been in Paris yesterday…”

Birmingham at night - the city is one of the UK's most polluted cities according to a report issued last year by the government. Photograph: iStock

Birmingham at night - the city is one of the UK's most polluted cities according to a report issued last year by the government. Photograph: iStock

Know your enemy

This lack of ownership of the problem can fuel our sense of powerlessness. Yet, knowledge is also power – it can give us the tools to reduce our risks, make different choices and demand more from our governments. Clean Air Day, the annual air pollution awareness event, which takes place every year in June, started life partly in response to the need to be clear about the facts.

In 2014, prime minister David Cameron went on Breakfast TV to tell viewers that the red dust on their cars and the choking air outside was due to ‘Saharan dust’, a “naturally occurring weather phenomenon.”

In fact, the desert dust was only present for a short time near the end of a 10-day pollution episode in March and April 2014. It mostly came from farmers fertilising their fields and industrial emissions from Europe, according to a scientific paper published in Environmental Research Letters two years later in 2016. “The pollution episode in spring 2014 was widely attributed to Saharan dust in the UK media, thus placing a (false) emphasis on a natural phenomenon, which cannot be addressed by policy action,” the scientists said.

So, understanding air pollution can help us hold our politicians to account and demand more from the governments we elect. There are many sources of information. Defra publishes a daily air pollution forecast for the whole of the UK here: uk-air.defra.gov.uk Data is supplied by the Met Office and is based on five key pollutants: ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide and PM2.5 and PM10 particles. Simply add your postcode to find out what pollution is like for that day on a scale of 1 to 10, 1 being low and 10 being the highest.

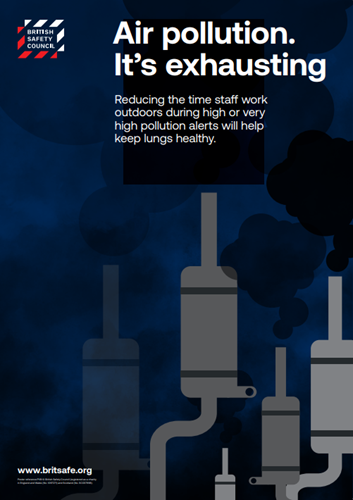

A poster produced for the British Safety Council's Time to Breathe campaign urges employers to take steps to protect outdoor workers during high pollution episodes. Photograph: British Safety Council

A poster produced for the British Safety Council's Time to Breathe campaign urges employers to take steps to protect outdoor workers during high pollution episodes. Photograph: British Safety Council

Small steps

Many of the people most at risk from air pollution exposure are least responsible for generating emissions. This means that changes in lifestyle by those who generate most air pollution can have a positive effect, even if small at the level of the individual. Transport for London, for example, advises drivers to take public transport or to cycle or walk during high pollution alerts, both to reduce overall emissions and for individuals to avoid higher levels of exposure: research has shown that pollution builds up inside cars to higher levels than the ambient environment.

Forty per cent of car journeys in England are less than two miles – each journey adds up. “The gains from leaving the car at home and walking, cycling or taking public transport for these short trips would transform our cities,” Fuller writes. “As you step out of your house and into your car, ask yourself if you could walk instead.”

Again, though limited in its benefits given elevated ambient pollution levels in our towns and cities, individuals can use various pollution apps like London Air to plan routes to reduce to some degree personal exposure as the levels of air pollution vary across urban spaces. For example, narrow, tall streets can see higher levels during stagnant weather. Or, kerbside pollution levels are higher than the surrounding area.

The Defra pollution forecast (provided by the Met Office) shows the air pollution level in your area (from very high to low pollution levels), which can be used to decide whether to exercise or undertake strenuous activity outside. Defra’s Daily Air Quality Index says that even during moderate levels of air pollution, “adults and children with lung problems, and adults with heart problems, who experience symptoms, should consider reducing strenuous physical activity, particularly outdoors.”

Simple tips like taking the back streets instead of walking beside a busy road can cut your exposure by half. It’s what Norman Nicholson the poet called “giving your own little push to the spin of the earth”. Yet far more is needed from government to communicate these messages.

Industry’s impact on the air

But our individual impact on the air is only part of the story. Businesses have a major impact on the quality of the air we breathe.

The construction industry takes a lion’s share and is responsible for 18 per cent of large particle pollution in the UK according to a 2022 report from Impact on Urban Health and the Centre for Low Emission Construction, a figure which rises to 30 per cent in London. Yet there is positive action even in this ‘dirtiest’ of industries.

In 2015, a construction ‘low emission zone’ was introduced in London. It required equipment over 10 years old to be replaced or retrofitted on all sites in central London and major developments in outer London. The Mayor wants to go further with a user-charging scheme akin to the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) with penalties for non-compliant plant and machinery.

Road vehicles are one of the biggest contributors to air pollution, producing nearly half of all nitrogen oxides. Photograph: iStock

Road vehicles are one of the biggest contributors to air pollution, producing nearly half of all nitrogen oxides. Photograph: iStock

It’s positive that the construction industry appears concerned about its air pollution impact. Last year, Impact on Urban Health spoke to the sector and 97 per cent told them air quality is an “extremely or very important environmental health concern”. This work led to a set of recommendations for businesses, local authorities, and government to reduce air pollution from construction sites. “We’re now supporting Lambeth and Southwark councils to implement those recommendations, for example by employing Compliance Officers in the London boroughs whose role is to make sure sites are complying with emissions standards,” explains Matt Towner, programme director of the health effects of air pollution programme at Impact on Urban Health.

Changing how we live

Change needs both individuals and leadership. Sometimes a campaigner such as Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah CBE cuts through to highlight an issue of public concern and can drive political, and ultimately regulatory action. Mums for Lungs again are part of a grassroots effort to gather citizens who are not experts in order to coalesce around efforts to change behaviour, such as stopping car idling. Leaving your engine running while stationary produces unnecessary air pollution and members of the group are given flyers to approach idling drivers – particularly outside schools – to talk about the impact of air pollution.

Impact on Urban Health’s work is also focused on engaging with and amplifying the voices of people who are most vulnerable to air pollution. A project is under way involving delivery drivers who often rely on their own personal motorbikes and scooters to deliver food.

Not only are these polluting vehicles bad for air quality (the social, environmental and health costs of diesel vans alone is over £2 billion) but they are dangerous for their drivers. “The project is ongoing, but the data we gather will help to make a case to on-demand food delivery companies that choosing cleaner, safer transport alternatives would be better for public health, for their workers, and ultimately for their business,” said Towner.

Impact on Urban Health is working with food delivery companies to switch to cargo bikes. Photograph: Honor Elliot

Impact on Urban Health is working with food delivery companies to switch to cargo bikes. Photograph: Honor Elliot

To make a lasting, positive impact though, committed individuals need to join up with those who have the greatest influence, whether in civil society, trade unions, or local and national government.

Streets for Kids, which works by prioritising cycling and closing off roads to cars where schools are, led to a 23 per cent reduction in nitrogen dioxide (NO2) in Brent, Enfield and Lambeth in London. If all feasible schools had School Streets, peak car trips would be reduced by up to 32 million per year, found research produced in 2021 for Possible and Mums for Lungs. Ersilia Verlinghieri, researcher at the University of Westminster, commented: “School Streets can help us promote that radical transformation we urgently need to address current health and climate emergencies appropriately.”

Conclusion

We have seen how individuals and businesses can be part of the fight back against air pollution. They need to come together to build the political will necessary to turn public concern into policy and real change. It’s a tough and ongoing battle. For example, ULEZ is currently subject to a judicial review against its expansion to cover all Greater London. A decision is due by August when the proposed changes are due to come in. There is continuous pushback everywhere, particularly as the economy is seen as a ‘vote winner’ over the environment.

The government is also seen as lacking in ambition, its recent targets for air quality trailing far behind our EU counterparts which recently agreed to work towards meeting the cleanest targets set by the WHO.

So, is air pollution a necessary evil? Towner believes not: “Air pollution is not inevitable. Time and time again research shows that air pollution can be fixed relatively quickly.”

Here we should turn to Des Wilson, a campaigner who showed that not only was change possible but necessary. His work on CLEAR, the Campaign for Lead Free Air, set up in 1981, led to the eventual ban of leaded fuel and the introduction of unleaded petrol in 1986.

In 2021, the use of leaded petrol finally ended with Algeria the last country to phase out the fuel, preventing more than one million premature deaths each year worldwide from heart disease, strokes and cancer.

FEATURES

Underpinning safety training with neuroscience for long lasting impact

By SSE Active Training Team (ATT) on 30 November 2025

A behavioural safety training programme developed by Active Training Team for energy provider SSE has been carefully designed with neuroscientific principles in mind – resulting in a prestigious industry award for Best Training Initiative in 2024.

Why a painted line will never be enough

By UK Material Handling Association (UKMHA) on 20 November 2025

Businesses that operate material handling equipment like forklifts are being urged to submit accident and near miss details to a new confidential reporting portal so the industry can identify what needs to be done to improve safety standards.

Why workplace transport training is changing in 2026 and what it means for employers

By AITT on 14 January 2026

New workplace transport training categories due in January mean it is essential to ensure operators of material handling equipment have the necessary training for the exact type of machine they use, and accredited training providers are an ideal source of advice and conversion training.