The Robens report, which established the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 (HSWA), is 50 this year. Safety Management celebrates Robens’s achievements and considers if the Act needs refreshing in the face of huge social changes.

Features

How Robens super-charged the safety system

“Robens has lit a fuse. His report will radically alter the whole structure of industrial safety,” said Safety Management (then Safety & Rescue) in 1972.

And no wonder. His thesis was explosive, blowing apart the current, broken system of health and safety and proposing wholesale, fundamental changes to employers’ duties, risk management and the inspectorate. His 80,000 word treatise remains the foundation on which the current system of occupational health and safety regulation in Britain today is built, embodied in the Health and Safety at Work Act (HSWA) 1974.

‘Something had to be done’

In 1969, Lord Alfred Robens, Baron of Woldingham, was selected by Labour politician Barbara Castle, then secretary of state for employment and productivity, to chair a committee on workplace health and safety. By the time work began in May 1970, the Conservatives were in power. But what had not changed was how dangerous work had become.

Newspapers told of people perishing in burning factories, the fire exits sealed to prevent theft at A. J. & S. Stern’s furniture factory in which 22 workers died in 1968. In Aberfan in 1966, a massive coal waste tip crashed down the mountainside of the Welsh mining village killing 28 adults and 116 children. In total, 1,000 people died each year in work-related accidents and half a million suffered injuries. Acts were introduced to grapple with the problems, including separate Acts covering safety in mines, agriculture, offices, shops and railway premises – but the deaths kept rising.

It was clear to everyone that the current approach wasn’t working, says Dr Mike Esbester, senior lecturer in history at the University of Portsmouth: “There was a sense of a need for something to be done – and I don’t just mean within the corridors of power at Westminster but in public attitudes too. Occupational health and safety is not very visible much of the time. Very often it happens in workplaces behind closed doors and yet, this is one where it did seep out into wider society and there was an awareness that the numbers of deaths, injuries, the amount of ill health and suffering that was being caused wasn’t ok.”

Every employer should identify the risks

The first major change Robens advised was to simplify the system. Gone was the “confusing tangle of statutes and regs” and in their place a single Act was introduced to apply to all workers. Six inspectorates were to become just one new authority for safety and health at work, the HSE. Robens’s core concept – in a move with far-reaching consequences – was that work, rather than a workplace, was the key determinant of risk. This meant that its principles could apply to anywhere work was done.

In his words the risk now lay with “those who create the risks and those who work with them”. This was ground-breaking, explains Lawrence Waterman, who chairs the British Safety Council’s campaigns committee. “Robens went away from listing lots of individual regulations telling you exactly what you ought to do about particular hazards and the risks that arise and made it a simple principle – goal setting – every employer should identify the risks that they’re generating and manage them effectively.”

Self-regulation

The other huge change was the shift to more self-regulation and a greater use of voluntary standards and codes of practice. This was perhaps counter-intuitive. There were fewer fines, but less complacency – employers didn’t wait for the knock on the door, they started to take action. “It made the system more flexible and fleet of foot,” says Lawrence. “It meant that instead of inspectors being bogged down with a load of court cases as the only way to drive change, there were new tools in the toolkit for regulatory enforcement such as Improvement Notices.”

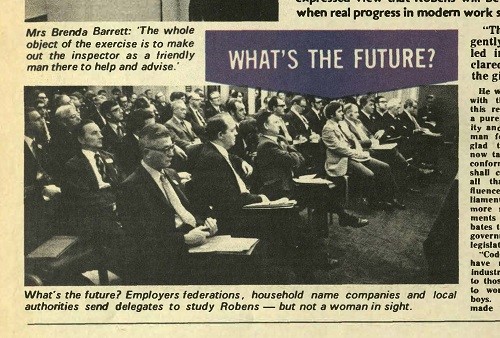

Coverage of the British Safety Council's conference held to discuss the Robens report on 6 September 1972. Photograph: British Safety Council archives

Coverage of the British Safety Council's conference held to discuss the Robens report on 6 September 1972. Photograph: British Safety Council archives

The British Safety Council hailed the system Robens proposed as the “biggest voluntary accident prevention service” and encouraged everyone to take part. “Until [Robens] the risks were identified by the legislators – often by counting bodies as a result of accidents – and then they made regulations,” explains Lawrence. “But what Robens did is he turned that the other way round. It seems to me that was the big impact – shifting the burden from the legislator to the employer.”

A movement is born

If the assignment of responsibility set the direction, it was the new duties for employers to consult with their workers and for unions to have a seat on HSE’s board, that provided the engine oil for change. David Eves joined HM Inspectors of Factories as an inspector in 1964.

He remembers how Robens’s recommendations on consultation, embodied in the HSWA, fuelled a surge in interest in health and safety and an exchange of ideas from all sides. “There was a steady increase after 1974 in invitations [to us inspectors] from the larger companies to address managers and explain and emphasise the importance of their new duties, and a corresponding growth in numbers of trained safety officers,” he recalls.

“A proactive, systems-based approach to health and safety management, accident and ill-health prevention began to be preferred by industrial leaders who were beginning to recognise the strength of the business case for improving health and safety performance.

“Soon, the involvement of employers, local authorities and trade unions, working together to develop policy in the new, tripartite Health and Safety Commission [the old strategic function of HSE] and its advisory committees, began creating a momentum for improvement in high-risk industries with a poor safety record, such as construction, and began to give meaning to the Robens concept of self-regulation.”

Today and beyond

Most of the people we spoke to believe that Robens’s principles are timeless. “The Act’s flexible approach and understanding that risk can change renders it mostly future-proof,” says David Ashton, HSE’s former deputy chief executive and director of field operations before retiring in 2014. “It’s also worth noting that Robens refers to the issues of mental health at work and risks from new technologies as already being serious concerns at that time. The ‘Robens philosophy’ was designed to cope with such issues.” Robens even addresses, presciently, home working, stating that the employer should provide “equipment and instruction for those [employees] who... undertake the work in their own homes”.

The question today, in its 50th anniversary year, is, are we making Robens’s ideas work for us? Robens spoke of his work as if it were a living project, not a flat document. “An inquiry is not about digging out the truth but digging it in,” he told our magazine. Does the HSWA Act reflect the big risks of our time and the nature of work? Do results show that we are making progress?

Lawrence Waterman: "Transparency, about companies’ health and safety performance… ought to be an important part of self-regulation."

Lawrence Waterman: "Transparency, about companies’ health and safety performance… ought to be an important part of self-regulation."

Today, and for every year of the past decade, 14,000 people still die of work-related lung disease. Work-related stress is also on the rise. Lawrence says health now needs greater focus in the HSWA: “Health needs to be looked at to make sure the kind of guidance we’ve had from people like Dame Carol Black is properly reflected in both the law and in the way it’s enacted by our regulator.”

The idea of the gig economy would not have crossed Robens’s mind, he adds: “Robens was really thinking about very conventional employment where you were likely to be employed for life.” The gig model severs the link between worker and employer, so old ideas of ownership of risk become more muddled. This needs to be challenged, as well as the many wellbeing and psychological health issues of having no fixed hours, according to Lawrence.

Robens in a complex world

Then there are ideas which were rejected at the time as unpalatable, but which now look modern and necessary. For example, the requirement for registered companies to publish their accidents and occupational diseases, as well as preventative measures taken, in their annual reports. This could be a powerful driver for companies to do better, says Lawrence: “Transparency, about companies’ health and safety performance… ought to be an important part of self-regulation because it involves shareholders being empowered to ask their boards questions about health and safety.”

So – Robens, 50 years on, still controversial, still relevant. But with a little dusting down and polishing to bring it up to speed to today. “A Robens retrospective is an example of looking back as a way of strengthening the way forward. We stand on Robens’s shoulders but that means we can see further,” states Lawrence.

A re-embracing of Robens would also need financial backing. “I don’t think that Robens, when he was drawing up his plans for health and safety, would have recognised the combination that we live in of a framework that is incredibly robust, and a regulatory system that has been starved of resources,” says Lawrence, who argues that more resources for coronavirus management in workplaces could have reduced the burden on the NHS. “At the moment we have a regulatory system that is structured really well, but the enforcement at the sharp end is letting the team down by not adequately intervening where it’s needed.”

A re-appraisal would also need recognition of the fact we are a different country now, with fewer unionised workplaces thanks to the decline in heavy industry. Is self-regulation based on the system energising itself still appropriate? The complexity of the task is arguably no different to the task faced by Robens in 1970. “The time now seems right for a debate about changes that might be required,” says David Ashton. “[Change] is surely no surprise after 50 years, and would be entirely in keeping with the original spirit of Robens – something he would have expected us to do, I suspect.”

FEATURES

How to mitigate the hearing loss cost escalation tsunami

By Peter Wilson, Industrial Noise and Vibration Centre (INVC) on 06 February 2026

Employers need to adopt the latest and most effective noise risk evaluation and management measures, or face rapidly-rising compensation claims for noise-induced hearing loss at work.

Young drivers and work-related road risk: why employers must act now

By Simon Turner, Driving for Better Business on 06 February 2026

Young drivers have a higher risk of being involved in road collisions due to factors such as their inexperience, so when employing them to drive for work, it is vital they receive the right support to help them grow into safe professionals behind the wheel.

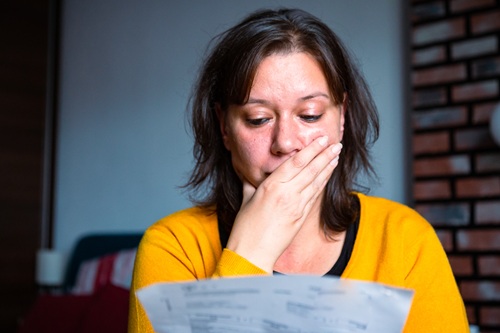

Financial stress: why and how it affects workplace safety

By Chloe Miller, freelance writer on 06 February 2026

Financial worries can lead to cognitive impairment that increases the risk of workplace accidents, so it’s essential employers provide financial education and confidential support for workers who may be struggling with problems like debt and unexpected living expenses.