With 31 million days lost to musculoskeletal conditions in the UK every year, protecting your back – or the backs of your employees – has never been more important.

Features

Musculoskeletal disorders: back at it

Many of the jobs in the oil and gas industry are physically demanding. If pain, for example, is left unattended, it can develop into serious musculoskeletal disorder.

The UK’s oil and gas industry employs approximately 283,000 people and many of the job roles are physically demanding, with employees spending significant periods of time standing, carrying out repetitive activities and operating heavy equipment, all of which can cause tension and stiffness in the lower back. If left unattended, these issues can develop into more serious musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) which may require treatment.

Some oil and gas workers are also likely to spend periods of time sitting at a desk or in front of a computer. Spending long periods of time sitting down is another common cause of back issues. Sitting for five hours a day, five days a week equates to 1,175 hours – or almost 50 days – every year.

Unfortunately, sitting for longer than 20 minutes has negative effects on your body, including an increase in musculoskeletal problems such as back and neck problems, while extended periods of sitting can affect the spine, neck and shoulders. This, in turn, can also affect the arms, elbows and wrists.

Oil and gas employees spend significant periods of time standing, carrying out repetitive activities and operating heavy equipment

Oil and gas employees spend significant periods of time standing, carrying out repetitive activities and operating heavy equipment

In order to prevent these negative effects, employees should move at regular intervals using the ‘20/20’ principle – 20 seconds away from the sitting position every 20 minutes. You should always try to stand/move every 20 to 30 minutes, even if only to walk a few paces.

Another way to avoid back problems is to adopt the correct sitting position; sitting incorrectly can cause back problems by putting extra pressure on various body parts.

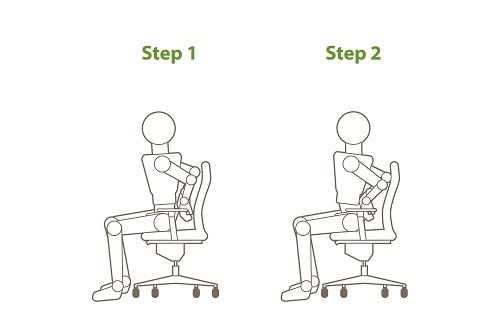

To sit correctly, you first need to become familiar with your optimal sitting position, which can be achieved by adjusting the height of your chair until your feet are flat on the floor and your feet and knees are a hip width apart. Starting with your feet together, turn your toes out as far as you can. Next, bring your heels level with your toes, then bring your knees in line with your feet and you will have reached the optimal position for your legs.

To set the lower part of the spine in a neutral position, sit on your chair with your hands on your hips, then rotate them as far forward as possible. Next, rotate the pelvis backwards as far as you can. With the pelvis in this position, place your rib cage in a straight line above the pelvis in order to make the lumbar spine curve slightly inwards. This is the optimal position for your spine.

You should always try to stand/move every 20 to 30 minutes, even if only to walk a few paces

You should always try to stand/move every 20 to 30 minutes, even if only to walk a few paces

To achieve a neutral position for the whole body while sitting, you should also ensure you aren’t leaning too far forward as this puts pressure on the lower neck as it is forced into flexion (as if looking down), whilst the upper part of the neck is forced into extension (as if looking up). To prevent this and attain your body’s neutral position, look straight ahead while tucking your chin back as if you are holding a small ball under your chin.

The most important thing to remember when sitting is to maintain the curvature of the lower spine. Your lower spine should curve away from the back of the chair and the best way to make sure this happens is to support it, either by purchasing a chair with lumbar support built-in or by placing cushions or a rolled-up towel at the base of the spine.

If you are unlucky enough to suffer a back injury, there are several exercises that can be carried out to increase mobility and reduce pain levels.

These include:

Lower back stretches

This simple exercise stretches out the tissue in the lower part of the back, alleviating pressure and stress on the area. To perform it:

- Sit on a chair and place your hands on the lower part of your back just above belt level

- Arch your back as you gently press with your hands to assist the movement

- Hold your back in this arched position for two seconds and then return to the start position

- Repeat five times.

A simple chair exercise stretches out the tissue in the lower part of the back

A simple chair exercise stretches out the tissue in the lower part of the back

Side bends

This exercise helps maintain movement in the lower back.

- Stand up tall with your arms on the outside of your thighs

- Slowly bend sideways by sliding one hand down one thigh towards the floor

- Slowly return to the upright position and repeat on the other side. Repeat five times. (See graphics below.)

If you are concerned about back pain, consider visiting a qualified physiotherapist who can help restore movement and function and reduce your risk of injury in the future. A pain-free back is of the utmost importance; ensuring it remains that way should be a priority for everyone.

FEATURES

Pursuing workplace wellbeing through authentic leadership

By Dr Audrey Fleming, British Safety Council on 26 April 2024

By being open, honest and vulnerable in their interactions at work – and genuinely seeking and valuing the input of employees – leaders can develop a workplace atmosphere where trust and respect flourish, in turn supporting the wellbeing, engagement and performance of their teams.

Out in the field: why lone worker monitoring is key

By Rebecca Pick, Pick Protection on 26 April 2024

People working away from a fixed base out in the field may need to quickly summon assistance in an emergency, but it’s important to choose the right communications and alarm technology for their needs.

Why line managers play a vital role in workplace wellbeing

By Marcus Herbert, British Safety Council on 03 September 2023

The behaviours of line managers can have a positive or negative impact on employee health, wellbeing and engagement, so it’s vital managers get staff feedback on whether their management style is supportive or negative, and have regular check-ins so workers can raise concerns about their wellbeing.